* (restored)

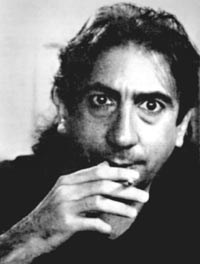

Néstor Perlongher, Poet, prose-writer, Gay Activist, and Anthropologist, (24 December 1949 Avellaneda, Buenos Aires- 26 November 1992 São Paulo).

“Perlongher’s work is full of fences, borders, edges crumbling or about to fall, in an orgy of words that slip, tear, handkerchiefs that unravel.” Jose Quiroga

The first poem I ever read by Néstor Perlongher was ‘How can we be so lovely’, translated by Steve Dolph, on his amazing journal of literature in translation, Calque. That poem had me totally hooked, the way the words slink and shimmy down the indentations and the way the language sprawls and shifts. Ever since reading ‘How can we be so lovely’, I’ve been scratching and itching for as much as I can get. I wrote to Steve, asking permission to include that poem here, as part of this Perlongher celebration. I could never have dreamed that I’d receive what I received back, an email telling me he’d been working on translations with CAConrad, and that he’d be happy to see some of them up on this blog. The selection that Steve and CA generously sent is reproduced below, with a short introduction by both translators.

NOTE: Blogger’s inability to handle indented lines (or my inability to render them in HTML) has led to me putting many of these poems up as JPEGs. However, if you click on them, you should be able to read them without much trouble. I really hope you enjoy the selection.

Poems by Néstor Perlongher, translated by Steve Dolph and CAConrad.

In Argentina during the 1970s, homosexuality was outlawed. The imprisonment, torture, blackmail and disappearance of gays and other moral “subversives” and “degenerates” was common practice normalized and enforced by the junta government’s Ministry of Morality. This wonky translation for the name of the federal police force’s Departamento de Moralidad is intentional—only in the Land of Oz or Ursula Le Guin is such an agency nameable without resorting to irony. When gay rights activist Néstor Perlongher was imprisoned in 1975 at the age of 26 for possession of narcotics he probably assumed he would be dead within a week, but not before undergoing a routine of “enhanced” interrogation techniques like getting a couple of fingers chopped off. Although Perlongher had been jailed many times before—either for cruising or just for looking like a maricón—this detainment, following a raid of his home, promised to be exceptionally brutal. Unlike many of his fellow degenerates, Perlongher survived this three-month imprisonment and began writing the poems that would be collected in Austria-Hungaria, his first book. Shortly after the book’s release in 1980, Perlongher was detained again and beaten severely. He left Argentina soon thereafter and pursued an advanced degree in urban anthropology at the University of Campinas, in São Paulo, Brasil. In 1987, Editorial Último Reino published Alambres (Wires), the source of the two poems translated here. Néstor Perlongher died of AIDS in 1992.

Freud once said, “Everywhere I go I find a poet has been there before me.” He was right about us of course, don’t mind me being bold in saying so, boldness another solid poet trait. When Steve Dolph first told me that the late Argentine poet Néstor Perlongher had become an anthropologist, my first thought was, “Well, that’s a bit redundant, but a terrific occupation for a poet!” I’m grateful to Steve for introducing me to Perlongher’s extraordinary poems, and for inviting me to assist him with some English translations. It’s no mistake Steve would choose me, since he was aware of my often queer-centered poetry, but not just queer, and not queer in the mainstream, bourgeois fashion, but a queerness from the streets: poverty, prostitution, drag queens, suicide, drugs, AIDS, and more poverty. It’s been a privilege to join with Steve in shaping Néstor Perlongher’s poems into English, tapping into the great voice of a poet now dead of AIDS, like many lovely voices I’ve known, and very much miss. I look forward to listening closely to Perlongher with Steve in the days to come as we continue to translate and shape these poems which are long overdue their translation into English, and long overdue their additional audience for new generations to come. If you don’t know the work of Néstor Perlongher, you should, in fact everyone should.

LAS TÍAS

y esa mitología de tías solteronas que intercambian los peines grasientos del sobrino: en la guerra: en la frontera: tías que peinan: tías que sin objeto ni destino: babas como lamé: laxas: se oxidan: y así ‘flotan’: flotan así, como esos peines que las tías de los muchachos en las guerras limpian: desengrasan, depilan: sin objeto: en los escapularios ese pubis enrollado de un niño que murió en la frontera, con el quepís torcido; y en las fotos las muecas de los niños en el pozo de la frontera entre las balas de la guerra y la mustia mirada de las tías: en los peines: engrasados y tiesos: así las babas que las tías desovan sobre el peine del muchacho que parte hacia la guerra y retocan su jopo: y ellas piensan: que ese peine engrasado por los pelos del pubis de ese muchacho muerto por las balas de un amor fronterizo guarda incluso los pelos de las manos del muchacho que muerto en la frontera de esa guerra amo-rosa se tocaba: ese jopo; y que los pelos, sucios, de ese muchacho, como un pubis caracoleante en los escapularios, recogidos del baño por la rauda partera, cogidos del bidet, en el momento en que ellos, solitarios, que recuerdan sus tías que murieron en los campos cruzados de la guerra, se retocan: los jopo; y las tías que mueren con el peine del muchacho que fue muerto en las garras del vicio fronterizo entre los dientes: muerden: degustan desdentadas la gomina de los pelos del peine de los chicos que parten a la muerte en la frontera, el vello despeinado.

//

THE UNCLES

Legend of the drag queen spinsters exchanging oily hair picks of boys from the border wars: sisters who comb: whores with purpose and reason their own: spit of gold: loose: aging fast: they strut and brag and clean picks of the boys at war: pluck, degrease: with purpose their own: tines that coiled pubic hair of a boy dead at the border, his cap contorted: photos of grimacing children on the borders running between guns of war and warmth of their withering spinster “uncles”: the hair picks: oiled stiff: retouch the boy’s bangs with spit before leaving for war: and they think: this pick oiled by groin of a boy killed by guns of a borderline love also holds hairs from the dead boy’s hand after he touched himself at the border of the amorous war: those bangs: the boy’s dirty hair, flaring pubis of the scapularies, taken from the bathroom by the swift midwife, plucked from the bidet at the moment they, in private, remember their spinster drag queens who died in the crossed camps of war, retouch their bangs, the spinsters who die with picks of the boys dead at the hands of the borderline vice between the teeth: bite: taste gels from hairs in the picks of kids who get off to their deaths at the border, the uncombed down.

EN EL REFORMATORIO

a Inés de Borbon Parma

O era ella que al entrar a ese reformatorio por la puerta de atrás veía una celadora desmayada: calesas de esa ventiluz: Inés, en los cojines de esa aterciopelada pesadumbre, picábase: hoy un borbón, mañana un parma. La hallaban así, yerta: borboteaba. Los chicos se vigilaban tiesos en su torno-y unos se acariciaban las pelotas debajo del bolsi- llo aunque estaba prohibido embolsar los nudillos, por el temor al limo, pero se suponía que la muerte, o sea esa languidez de celadora a lo cuan larga era en el pasillo, les daba pie para ello; y asimismo, esta mujer, al caer, había olvidado recoger su ruedo, que quedaba flotando – como el pliegue de una bandera acampanada-a la altura del muslo; era a esa altura que los muchachos atisbaban, nudosos, los visillos; y ella, al entrar, vio eso, que yacía entre un montón de niños – y el más pillo, como quien disimula, rasuraba el pescuezo de la inane con una bola de billar; y un brillo, un laminoso brillo se abría paso entre esa multitud de niños yertos, en un reformatorio, donde la celadora repartía, con un palillo de mondar, los éritros: o sea las alitas de esas larvas que habían sido sorprendidas cuando, al entrar en la jaula, se miraban, deseosas, los bolsillos; o era una letanía la que ella musitaba, tardía, cuando al entrar al circo vio caer ante sí a esos dos, o tres, niños, enlazados: uno tenía los ojos en blanco y le habían rebanado las nalgas con un hojita de afeitar; el otro, la miraba callado.

//

IN THE ASYLUM

to Inés de Borbon Parma

Entering the back door of the asylum she saw the passed out woman: the guard: the ventilated bonnet: in her velveted grief Inés shot dope on the cushions: today a Borbon, tomorrow a Parma. They found her rigid and drained. The remote eyes of the boys watched each other – some stroked their balls through their pockets though it was against the rules to knuckle your bag, for fear of the cum, but they figured death, or maybe the lazy guard stretched in the corridor was their reason for it; and likewise, this woman, when she fell, failed to gather her slip, which floated – like the folds of a flag – at the top of her thigh, where the boys stared, where it was knotted like a curtain; and she, when entering, saw this, lying between a group of boys – and the most insolent one, rogue that he was, shaved the dope’s nape smooth as a billiard ball; and polished with a laminose polish that opened a path in the horde of dirty boys, in the asylum, where the guard dispensed reds with a toothpick: and maybe the flying worms had been surprised when entering the cage, seeing fists squirm in pockets with lust; or was it a slow litany she murmured, and when entering their circle saw fall in front of her two, or three boys linked up: one’s eyes rolled back, and they had sliced his ass with a razor; the other watched her in silence.

All translations above by Steve Dolph and CAConrad.

“Throughout his work Perlongher seeks a fluid, non-binary persona in drift, in an incessant process of becoming, very much in line with Deleuze’s theories. Perlongher moves on the margins outside of the norm, be it the literary norm or the patriarchal societal and political stratification of his time. When homosexuality ceases to be a deviant marginality and is co-opted by society, with desire controlled by permissible behaviours (in light of the AIDS epidemic), Perlongher turns increasingly to a nomadic voice in constant flux and ultimately to the abandonment of the individual self into a larger, mystical unity.” Marlene Gottlieb.

Perlongher was regularly published in the journal of Argentinian Poetry XUL which is archived on-line. These poems translated in English from XUL are available on-line:

‘(degradée)’

Tuyú

Mme. Schoklender

Circus

The scandal of Evita Vive (a collection of short stories published 1989)

In an essay on the importance of transvestism to Perlongher’s poetry, Ben Bollig recounts the scandal surrounding the publication of Evita Vive:

‘In 1989, a public scandal occurred around the publication in the Buenos Aires review El porteno of his short story ‘Evita vive’, in which Eva Peron returns post-mortem to a world of drug dealers, homosexuals and male prostitutes. Peronist councillors in Buenos Aires called for the sequestration of the publication, while the editors received telephone death threats against the ‘travestis’ allegedly working there.’ Ben Bollig.

An English translation translated by the Canadian poet E.A.Lacey is included in ‘My deep dark pain is love: Latin American Gay Fiction’ (Winston Leyland ed. Gay Sunshine Press 1993)

Lacey points out in a footnote that the title ‘Evita Vive’ is a subversive take on the Peronist slogan ‘Evita Vive’, i.e. ‘Evita Lives’, which piggy-backed Evita’s iconic status to a wide range of situations: ‘Evita Lives in the proletarian slums’ etc.

extract from Evita Lives, translated by E.A. Lacey:

‘I met Evita here in a hotel in the red-light district of Buenos Aires. It was so many years ago! I was living- well, I was living with a black sailor who’d picked me up as I was cruising the port. I remember it was a summer night- maybe in February- and it was very hot. I was working in a night-club, at the cash register, until three in the morning. But that particular night, I had a fight with Lelé, a jealous little queen who was always trying to steal my tricks- and we started fighting and pulling each others hair behind the bar counter, and just then the owner comes along and says: “Three days off for making such a racket.” I didn’t care, I went right back to my room, I open the door… and there she is with the sailor. Of course, I was mad at first; besides, I was already furious after my fight with the other queen; I almost jumped on her without even looking to see who it was, but the black man- who was a really sweet guy- gave me a real sexy look and said something like “Come on, there’s enough for you too.” Well, he really wasn’t lying because actually I used to give up with him, I’d get so tired, when he was still raring to go, but at the start, I dunno, I guess because I was jealous, because it was my home and so on, I said to him, “Okay, okay, but who’s she?”The sailor bit his lip because he saw that I’d got all upset, and in those days when I got angry I was a holy terror- nowadays not so much, I dunno, I’m more at peace with the world and myself. But in those days, I was what you’d call a real mean bitch queen, the kind you don’t want to provoke. And she answered me, looking me right in the eye (up till then, she’d had her head between the black man’s legs, and I hadn’t caught a very good glimpse of her, of course, because the room was in darkness). She said to me: “What? Don’t you recognise me? I’m Evita.” “Evita?” I said, because I couldn’t believe it. “You’re Evita?” and I turned the light on right in her face. And she was Evita, all right, you couldn’t mistake her, with that glossy, shiny skin of hers and the blotches of cancer underneath and- to tell the truth- they really didn’t look bad on her. I didn’t know what to say, but of course I wasn’t going to act like some silly hick queen who goes into a tizzy because of an unexpected visit. “Evita, darling”- I put my brain to work- “wouldn’t you like a little Cointreau?” (I knew she loved expensive drinks). “Don’t worry about that, darling,” she said, “we have better things to do now, don’t we?” “But listen, darling,” I said to her, “tell me, at least, how long have you two known each other?” “Oh for a long time, dear, for a long time, almost since Africa.” (Later Jimmy told me that he’d met her only an hour earlier, but these are trivial matters that don’t affect her personality at all: she was so beautiful!) “D’you want me to tell you how everything happened, dear?” I was really eager to know; after all, I had my bed companion for the night there and willing anyhow. “Yes, yes, Evita love, don’t you want a cigarette?” but I never found out the details of that story of hers (or maybe jimmy lied to me, I never was sure), because Jimmy got sick of so much chitchat and said “Okay, that’s enough,” and he grabbed her head- that bun she wore on top as an ornament, and it was all undone- and he put it between his legs, and really I don’t know if I remember her or him better, because I’m such a whore, , but I’m not going to talk about him now, all I can say is that that sailor was so sexy that day he made me squeel like a stuck pig, and he covered me with love-bites. Anyhow, next day she stayed for breakfast, and when Jimmy went out to buy some rolls, she told me she was very happy, and asked if I didn’t want to go to heaven with her, she said it was full of black men and blonds and guys like that. I didn’t really believe her, because if that was true, what was she doing coming looking for them, and on Reconquista street at that, don’t you agree, but I didn’t say anything, it was none of my business; I just told her, no, that I was all right, right then, living with Jimmy (today, I’d have said you have to “live an experience through to the end” but that expression wasn’t in vogue then), and I told her that if anything came up she should call me on the phone, because you never know, with sailors. Or with generals, I remember she said to me, and she sounded a little bit sad. Then we drank milk together, and she left. She left me a handkerchief, and I kept it for years, it was all embroidered with gold thread, but then somebody took it, I never knew who it was (there’ve been so many, many men in my life). The handkerchief said “Evita”, and it had the design of a boat on it. What do I remember about her? Well, she had long nails painted very green- at that time that was a mosrt unusual colour for nails- and she cut them off, she cut them so that the black man’s enormous cock could go deeper and deeper inside me, and she nibbled his tits and he came, that was the way he enjoyed coming most.’

“Perlongher’s aesthetic concerns appear sonic (“suena”) and visual (“brillar”); moral and semantic concerns are not mentioned. The flow of the poem, never wholly regulated or controlled by the writer, is closely related to “energiá: aché (la fuerza en el paganismo afro)” (Perlongher 1997b:16). We are moving here towards a strong relationship between the poem, the body, and “energy”.

The energy in Perlongher’s poetry seems to move between two polar concepts: the flow of writing (or drift, or wandering) and the care of revision and rejection. This is problematised by Perlongher’s attitude to the individual, an attitude perpetually informed by the possibility that “no hay un ‘yo’” (Perlongher 1997b:20).” Ben Bollig

Much of the following paragraph is cribbed, summarized and translated from Marcelo Manuel Benitez’s article: ‘A Militant of Desire’.

‘We don’t want to be freed; we want to free you!’ one of Perlongher’s daring Gay Liberation Front Slogans.

Perlongher was politically active on the student assembly of the labor party, where he was effective at slogan-writing and a fearlessly militant campaigner. He soon clashed with leaders over his overt homosexuality. He resigned from the labor party over their bigotry and sexism. Perlongher was then one of the founding members of the Gay Liberation Front, which worked closely with the Feminist Liberation Movement. One of the most noticeable features of Gay Liberation Front was their vociferous support of Worker’s Strikes and Student Protests. Perlongher was always adamant that the treatment of homosexuality was part of a wider social crisis that should be addressed in the same breath. Benitez also stresses the importance of ‘effeminacy’ to Perlongher’s politics (and by implication his poetics), as he challenged the widely held view among social activists that gay men ought to present themselves as ‘manly’ as other men, which led to discrimination and persecution of transvestites and transgender. Perlongher’s relationship with the Gay Liberation Front also became strained over their early support of Perón’s third term, which Perlongher disaproved of. In 1976 Perlongher was arrested and prosecuted. I can’t work out quite how long he was imprisoned but it is described as ‘not long but traumatic’. In 1981, bankrupt, Perlongher emigrated to São Paulo and left organized politics, continuing his struggle poetically. He died in 1992, from AIDS.

Perlongher wrote groundbreaking book-length studies of AIDS and Male Prostitution, neither of which have been translated.

Websites on Perlongher:

Wikipedia (in English)

Perlongher page at Elortiba (in Spanish)

Perlongher page at Literatura Argentina Contemporanea

Amazon Links to Books in English:

Ben Bollig: ‘Néstor Perlongher: The Poetic Search for an Argentine Marginal Voice’

The XUL Reader: An Anthology of Argentine Poetry (1980-1996)

Film:

Trailer

Documentary about Perlongher by Jorge Barneau (Youtube, in Spanish)

*

p.s. Hey. Here’s a finely guest-edited and finely oriented plus resurrected post for you today. Enjoy! Oh, and the p.s. (aka I) will return live again on Monday.

Now available in North America

Now available in North America

Last night was marvelous. Surprised and of course greatly pleased to see such a loud and attentive crow. I think they reall “got” PGL whch is first and foremost a work of moods and random, often contradictory emotion set against a backdrop of truly lovely Images,

If you separate all the elemts its sounds as if it should be a depressing experience but it’s not. Out anti-hero, perfectly played by Benjamin Sulpice (a real find) may be depressed and suicidal but he doesn’t act that way. e’re told that a serious accident that took place before the action begins has changed him. He clearly saw death and is tempted to revisit. But the concept of suicide doesn’t agree with him. He wants to “disappear’ and leave no trace. His friends listen sympathetically but their all on the edge of depression. Two suicides take place in the curse of the action, but they’re filmed as if they were Art Installations and seemingly judged as such by our anti-hero. There I sno formal score. The music we hear is entirely diegetic. It’s all tantalizingly off-balance. While Bresson is an obvious touchstone (especially “Le Diable Probablement”) Dennis and Zack don’t use their actor’s bodies the way Bresson did. They’re simply handsome boys in a Tati-like landscape of pretty suburban houses.

I thought of Sofia Coppola’s “The Virgin Suicides” and Godard’s “Pierrot le Fou”

Much more to say as I turn the film over in my mind.

d-

so good to finally get to pick yr brain in person. sorry if i get a little irritating in person. i’m kinda hyper and also kinda hate myself so i assume that everyone else thinks i’m as annoying and stupid to be around as i do. so thanks for being gracious and awesome.

i know i probably said it like a million times last night, but PGL was AMAZING and i can’t wait to show it to everyone i know.

heading back up the mountain now. i think my roommate is mad at me, or maybe he’s just mad that our pipes keep freezing and he apparently hasn’t been able to take a shower for like five days. i overthink the shit out of everything, though, so for all i know, shit could be just fine and i’m just being paranoid/looking for reasons to beat myself up.

i was kicking around the idea of coming back down on my days off next week, but i don’t think i’m gonna do it. i think i mentioned, but my roommate has a son, and part of the reason my rent is so low is because i do a fair chunk of babysitting. i don’t mind, gunner’s a great kid. loves to read and he’s really smart and he also loves ‘bob’s burgers,’ which is probably my favorite tv series out right now. you should check it out if you get the time while you’re in town. also, i wouldn’t want to be an imposition and i don’t think i can afford to leave town again since i have to refill my meds this week. but it’s a nice thought anyway.

i am pretty hungover today. would have had to leave by like 415 in the morning to catch the first bus up the mountain, so i decided to sleep in. i would say come visit me in big bear, but i don’t have anywhere you could stay and it’s expensive right now with all the snow and everything. lots of fucking flatlanders, and they ruin everything, those can’t-drive-ass-terrible-snowboarding motherfuckers.

do have loads of fun while you’re in town. i’m pretty jealous, because i have to spend my weekend making food for fucking ingrates. oh! i was so excited about the film that i forgot to tell you about this boy at my work that i kinda have a crush on. not a coworker. he’s a regular, so i’m assuming local. i’m telling you, if you saw this boy, you would lose yr shit too. he’s that cute. it’ll probably come to nothing anyway. he’s probably straight. did i ever tell you about how every time i let myself be stupid enough to be attracted to someone, he or she almost always ends up being straight or a lesbian, respectively? it sucks.

ok. well have lots of fun. i love you. not like boyfriends or something stupid like that, just that yr work means so much to me and our correspondence is very important to me and i really treasure yr friendship. and thanks again for being so awesome last night and not telling me to fuck off even though i’m sure you wanted to. don’t worry about it. talk soon.

-c.

What a great, great, great day this is. Congrats to both guest contributors on this one! Hope LA was Los Awesome.

J

The Néstor Perlongher story is a sad but oddly inspiring one.

Did I speak with you last night, rewritedept ?

i don’t know that we spoke. i saw joel, was looking for tosh but i guess he didn’t make it down. did you sit like front/center? cuz i wanna say you sat right in front of me, but i also fucked up and got far too stoned before i got there, and i usually get really paranoid and anti-social when i get too high. but yeah, i was the guy who asked the two rambling questions at the start of the audience bit.

Cadáveres in published in English by Cardboard House Press, translated by Roberto Echavarren and Donald Wellman.